The Fruits of Insanity: February in the Kenai Fjords

Last modified: 13th February 2020

an essay written by Erin McKittrick in 2007

I set aside my soaking gloves to arrange the sleeping bag under our thin grey tarp. An unmistakable mist of tiny drops sprayed the backs of my already freezing hands.

“It’s raining inside our shelter.” I complained, attempting to inject a note of humor into our misery. “Why is it raining inside our shelter?”

“Well, the tarp is set up flatter than usual…” Hig began, thinking.

“But we’ve been camping under silnylon tarps for years,” I interjected, before he could finish his thought. “It’s certainly rained before. And the rain always stayed outside the tarp.”

“And we’re right under a tall tree,” Hig continued, “so the raindrops falling on our tarp are larger. More pressure.”

“So they can squeeze right through instead of rolling down?”

“I guess. At least it’s raining less in there than it is out here. Lets get in.”

Hig climbed in, and I followed, after taking several minutes to do a ridiculous bouncing dance, gathering extra body heat for the long night ahead.

I stripped off my soaking raingear and crouched awkwardly on the edge of one of the rafts, trying to figure out which layer I was supposed to stick my feet into. Our bed was a strange mishmash of insulation, consisting of one carefully constructed summer-weight bag, and a bunch of hacked up bits of fleece and thinsulate bridging the gap between summer and February. Making our own gear often provides us with stuff better suited to our needs than anything we could find in the store. And when we run out of time for it, making our own gear often provides us with stuff more slap-dash and second-rate than anything we could find in the store.

We squirmed around in our strange bed, trying to stay balanced on the partially-inflated rafts, as the moisture slowly soaked from our wet clothes into the sleeping bag. I located a huge block of cheddar cheese in one of the food bags at the head of our bed, and wriggled out far enough to gnaw on it.

“One good thing about winter, anyway,” I proclaimed. “Dinner in bed. Don’t need to worry about keeping food away from the bears.”

“Or getting bitten by mosquitoes,” Hig pointed out.

Truthfully, I was beginning to think the bears had the right idea, sleeping through this miserable winter. This was only the fifth day of what was supposed to be a two week trip. It seemed like everything we were carrying was either broken, ill-designed, or both. It was raining inside our shelter. Hig’s new paddle was missing a large chunk from where it had collided with a rock.

In this wet weather, our cozy winter boots were merely heavy sponges on our feet, dragging us along a route that seemed to be nothing but obstacles. The logging roads leading across the peninsula were an ordeal of slushy rotten snow and twisted alder. Rocky River, our alternate route, was too thawed to walk on, but not quite thawed enough to raft.

“I don’t think we’re going to make it to Gore Point,” I ventured glumly, hoping to be talked out of my skepticism. “Not at this rate.”

“That depends,” Hig replied. “If Rocky River is broken up tomorrow to raft down, and if the paddling is okay… We may be going a whole lot faster.”

“But we’ve already wasted three days. We’re not even as far from the cabin as we were when we turned back the second day. And it took us almost all day to get here from the cabin.”

“You know, we could go back,” Hig offered. “We don’t have to go to Gore Point. I bet we could find some cool day hikes and shorter trips to do around Seldovia that would still make a fun vacation.”

“But the whole point of coming here was to go to Gore Point again and see the outer coast in the winter!” I protested. “If we don’t get out there, then all this crap;” I gestured at the slushy and rainy world outside, “is pointless.”

Gore Point is a steep rib of coastline, jutting into the stormy Pacific at the western edge of the Kenai Fjords. Separated from the rest of the peninsula by an array of steep and glaciated mountains, Gore Point is barely accessible by land, and far from civilization by water. Most of it’s infrequent visitors are fishermen landing on the sole protected beach. Hig’s obsession with this place started in childhood, listening to his fisherman father tell stories of the storm-battered beaches.

A year and a half earlier, on our way through the Kenai Fjords, we’d spent a week at a beach on Gore Point’s eastern shore. It was a mile long stretch of surf and sand, framed all around by towering cliffs, and looking straight out across the Pacific. Crisscrossed logs piled up at the top of the beach where the storms had left them, draped with fishing nets and buoys, rotting into nothing as they stretched back into the forest.

We caught rockfish from the schools near the cliffs, and startled cormorants out of their caves. Fat mountain goats ambled easily across the improbably steep slopes, and we followed their trails through the forest. We smoked fish, gathered huckleberries, split cedar shingles for our driftwood shelter, and raided an old shipwreck for flour and baking mix. We were there for a week, and even as we paddled away, we were planning for our return. After all, it was only a few days walk and paddle from Seldovia.

However, that “few days walk and paddle” was a summer calculation. Getting out there in February was proving much more complicated.

The next morning, we crawled back into our wet clothes, took down camp in a thick flurry of snow, and discussed our options, dancing and jogging in an attempt to get warm. Hig has an impressive tolerance for discomfort and cold. I have an impressive streak of stubbornness. Neither of us is sensible. So we waded into the knee-deep slush along the banks to launch our rafts in the half-frozen river, heading for Gore Point.

The rafts floated through weirdly green water, running over ice just a foot beneath the surface. Every few minutes we’d hit an ice dam, and perform an odd form of seated acrobatics with raft and paddle to wriggle over it. But inevitably, we hit a dam that was simply too big.

I paddled over to the water’s edge and let my raft rest there for minute, thinking about the moment when I would have to plunge my already freezing feet into the knee-deep slush.

“I hate slush,” I commented dully.

Hig glanced back at me from where he was wading up the hill. I gave him a pleading look. After all, his feet were already mired in the slush….

He answered my silent question with a smile. “Here, I’ll give you a tug over. Just let me put down my raft.”

“That would be absolutely awesome,” I replied fervently. “Thank you.”

He grabbed the bow line of my raft and pulled me up over the small rise. With a push, I was sliding down the other side, hitting the water with a gentle splash. My feet were still freezing.

In preparing for the trip, we had blithely assumed that the journey out to the coast would pose no real problems. All our worries were focused on the crossing. To reach Gore Point, we needed to paddle at least two miles across a fjord open to the Pacific Ocean. And as we were planning our trip, we obsessed over this crossing. There would be no land between us and the ocean to block any of the swell. Packraft landing spots would be few and far between, and possibly battered by surf. We were traveling in the stormy winter, to a place known for its storms.

Our rafts bobbed gently on three foot swells. Two days after our float down the Rocky River, we seemed to have left both the slush and rain behind. Scattered spots of sunlight lit up nearby peaks and occasionally passed over us, bringing a touch of golden warmth. Staring out toward the open Pacific Ocean, we could see the sunlit waves glinting on the horizon. We sang, to break up the monotony of the open water.

On the other side, I gathered twigs from the gnarled and wind-sculpted snags, and we cooked dinner, watching the harbor seals play in our protected cove.

“It’s a good thing no one else came with us on this trip, after all,” I commented. “We’d never have kept going.”

“Yeah,” Hig agreed. “I think if anyone else was here, we would have definitely turned around at Rocky River. It would have been the sane thing to do…”

“Insanity has it’s benefits, I guess,” I shrugged. “But I knew it would get nice again. That’s the thing about trekking. Nothing lasts forever. No matter how awful the weather or the bushwhacking, or whatever, it always does get wonderful again.”

The sunlight drifted down through the mossy trees as we snowshoed up a low ridge the next morning. It was a beautiful day. The snow was crisp and firm. From there, it should have been an easy downhill stroll through the forest to Gore Point beach.

But there was a more interesting way. Three hours later, I was crouched on the rounded edge of an icy peak, fingertips and toes clutching at the thin crust of snow, hoping not to be blown off the mountain. The wind was roaring past my ears. It was whistling and howling, gusting and screaming. Every loud and violent thing the wind could do, it was doing here. In the most exposed spots, I was reduced to a crawl, for fear of being blown off the mountain. There was nowhere to really be blown to, since the only sharp drop-off was on the windward side. But there was nowhere to stand up either, and the screaming of the wind in my ears drowned out all rational assessments of safety. It felt like nowhere a person should be.

From the peak, I held with a death grip to the trunk of a wind-stunted spruce, looking down at the white capped waves. It was foggy and stormy on the ocean side of the ridge, and the cliffs dropped almost straight down to the beach 1500 feet below us. If we’d taken the sensible route, we could have been there already. But we thought the ridgeline detour would give us better views. The view was certainly breathtaking.

But our winter boots had little traction on the icy-thin crust of snow, and with the wind blowing us over, there was little margin of error for scrambling on the narrow ridge. We couldn’t follow it any further, and were forced to retreat down and away from the howling wind, moving at the fastest creep we could manage.

We slid back down through the wind-stunted forest, gave up a depressing couple hundred feet of elevation, and began slogging through a steep traverse, headed to a less steep spot to climb back over the ridge, and down to the beach.

Hours later, in the last remnants of daylight, we were wriggling into the dilapidated driftwood shelter we’d built on the beach over a year ago, setting a hot fire in the jerry-rigged barrel stove. Our pilgrimage was complete.

The next morning, a cold fog streamed out over the forest from the frozen Gore Point Lake, meeting the mist that formed over the crashing surf. The sun rising over the ocean turned them both golden, and the colorful reflections of the hills and sky contrasted with the smooth grey sand at our feet. Gore Point was as wonderful in February as it had been in September.

Night fell clear and moonless. We scrambled over the pile of ice-slicked logs at the edge of the forest, out onto the sand flats. The tide was out beyond our sight, but we could still hear the crashing surf. From the forest, a pack of coyotes added their eerie high-pitched yelping and screeching to the sounds of the ocean. Holding hands, we stared up to admire the stars, pointing out the constellations, shivering a little in the cold. I wished I could stretch out this moment for at least another week. But the long and difficult return journey was weighing on our minds. We couldn’t afford to linger.

Looking up at the sparkling sky, we twirled in place a few times, making ourselves dizzy. Then we scurried back to the warmth of the fire, and repaired gear for our return.

We took the less scenic route back to our previously anticlimactic crossing. But unfortunately, the sea had no intention of being kind to us twice. The wind was howling out the mouth of the bay, hitting us broadside, racing for the ocean. The farther we got into the channel, the faster it blew. And there was sleet. It drove at us sideways, running down into our boats despite the spray skirts. We were decked out in our full set of homemade regalia - a fleece suit topped by a fleece hoodie, topped by a Gore-Tex rain suit, topped by a thermarest modified to be usable as a life vest, topped by a loose poncho-like dress of silnylon. The effect of the last two items, particularly, gave Hig the look of a boxy-looking football player in a Hefty trash bag. We were still soaked.

My packraft was bouncing in the swell and the waves. I squinted against the sleet in my eyes, and paddled ahead doggedly, aiming towards the point at the edge of the bay. The waves crashed and reflected off the rocks, building themselves even larger. Wind currents eddied around the point like water currents in a rapid, sending deafening gusts crashing into us. They cut off the tops of all the white-capped waves as they flew over the water. There was nothing to do but brace for the impact, pointing into the wind, and paddling hard not to be swept back the way we had come.

When the largest gust hit, I let out a scream, half fear and half exhilaration. Though he was only a few feet away, I wasn’t sure if Hig had even heard me.

These are the moments we call intrepid - miserable, frightening, but also alive and exciting. Intrepid moments are best taken in small doses.

We made it across the first small bay and around the corner. The mountains blocked a good part of the wind. Suddenly I could hear again. But we didn’t need to speak. There was no way we were trying the second, longer chunk of the crossing in this weather. We retreated to the beach, a fire, hot food, and a long sleep. In the rhythm of the winter days, fourteen hours of sleep begins to feel normal. And in the morning, the ocean presented a friendlier face.

We rode gently following seas to the head of Port Dick, surrounded by birds and otters taking shelter in the long protected fjord. Dozens of swans shied away from us, lifting off when they were barely white footballs in the distance. They flew straight at us, trumpeting loudly and circling our boats before peeling away.

The next day we were back on snowshoes, crunching through the forest and approaching the logging roads that would take us home. We stopped to eat a few handfuls of nuts, enjoying the sunshine. After almost two weeks out, nuts were pretty much all we had left.

“You know,” Hig said, looking at the map, “we could go back over Red Mountain instead. It would be really pretty up there in the winter, and we wouldn’t have to follow the logging roads”

“I don’t know,” I replied skeptically. “I mean, I don’t like the logging roads either. Even if they’re not as bad now that it’s frozen, they’re still boring. But I don’t know… How much farther is it?”

“Only a couple miles. But its 2500 feet higher,” he conceded. “And I wouldn’t want to be up there if it got stormy again.”

“Yeah. And we don’t know what the other side of the valley will be like to travel. Or the snow conditions. But it would sure be awesome today…”

“You know,” Hig said, “I think we should probably just head home. It’s been a good trip, but we’ve had enough adventures.”

“Yeah,” I agreed. “And besides, we can stop in the cabin again if we go back the same way.”

We started walking, crunching along over the craters left by moose tracks on the old logging roads. The sun glinted on the snowy peaks around us. It was only a few minutes before we stopped again.

“I’ve changed my mind. I mean, it’s totally fine if we just go home, but I really would like to go over Red Mountain.”

He grinned at me. “I was thinking the same thing.”

“I guess we never do learn…”

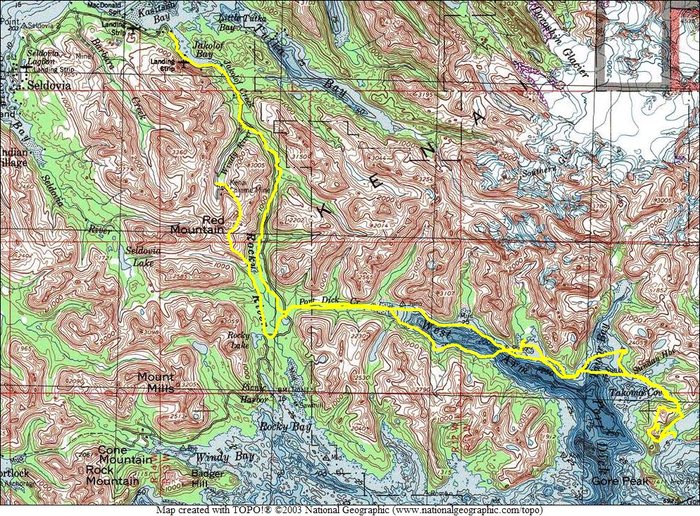

GORE POINT MAP

—

<a class="figure-caption__link" href="/photos/gore-point-map/">Get Photo</a></figcaption></figure> Created: Jan. 19, 2018